Allais paradox

The Allais paradox (after Maurice Allais ) is an experimentally observable violation of the independence axiom (English common Consequence effect, CCE) the economics decision theory. This means that the Hinzu-/Wegnahme of common consequences of a decision shall not alter the preference of the decision maker.

Structure of the experiment

The basic structure of the experiment is that subjects who twice from two lotteries:

Selection 1:

That means: You win 2500 monetary units (GE) with 33 % probability, 2400 GE with 66 % probability, with 1% probability one goes home empty-handed.

This means a sure win of 2400 GE.

Selection 2

These same people have then to make a further selection:

,

So 2500 GE with 33 % probability, nothing else.

,

So 2400 GE with 34% probability, nothing else.

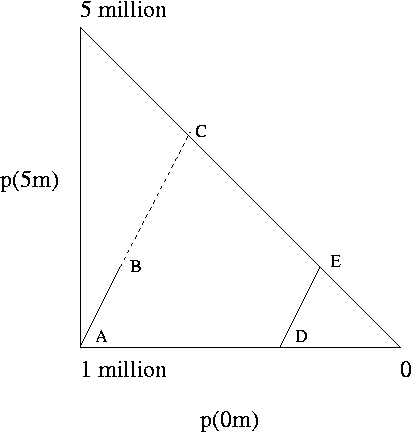

The four lotteries in a table:

The decision situation between a and b and between a 'and b' only in that in the former, a high probability for a gain of 2400 is that does not exist in the latter ( this is however not decided differs, it only makes the ' environment '). Otherwise, the situations are the same. After the independence axiom of the content of the first line should have no influence on the decision-making behavior.

Evaluation

The majority of subjects in the experiment chooses B and A ', therefore, the preferences are a < b and a '> b '.

Means:

Means:

These two inequalities can be combined to transform:

And

,

Two contradictory statements.

This contradiction can be explained by the fact that at the first decision between and the probabilities are at the forefront, with this when deciding between and hardly differ and the profits are used as the final criterion.

The experiment of Allais, published in 1953, represents an early example of the use of experimental methods to knowledge in economics and contributed to the development of experimental economics at.

Explanation

The psychological explanation for this irrational behavior provides the security effect, an aspect of the Prospect Theory of Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman. Kahneman gives the following example:

0.61 probability to win $ 520,000, or 0.63 probability to win $ 500,000

Here, the majority of respondents opt for the first option, since the difference of $ 20,000 makes more impression than the probability difference of 0.02. Even mathematically, this is the rational decision, because the expectation values of the two options are 317 200 versus 315 000.

Now you increase the probability of winning for both options 0.37 and provides the following lotteries:

0.98 probability to win $ 520,000, or sure win (probability 1) of $ 500,000.

Although the expected utility of the first option is now even bigger than before, replace the majority of respondents now paradoxically the second option. Now predominates as a decision criterion, the certainty of the smaller profit; it attacks the security effect. The expectation values of the two options are now 509 600 versus 500 000. Opposite the selection 1, the expected value of the first option of selection 2 to 192,400 has increased, that of the second option only to 185,000.

Alternative explanations

The simple heuristic "Take the Best" (see Gerd Gigerenzer ) provides a plausible explanation that does not require the mental calculation of probabilities. "Take the Best" can be summarized as follows: Take the best criterion and decide - if there is no relevant difference, take the second best, and so on.

Applied to the Allais paradox is this: When comparing between a and b, the probability is used as a criterion in the comparison between a 'and b', however, the expected profit.

See also

- Ellsberg paradox